Forget pressing. Stop worrying about the increased emphasis on the half half-spaces. Free eights? Pssh. Keepers comfortable with the ball at their feet? I'll pass. Center-backs who need to contribute to the attack and defend space rather than their own penalty area? Zzzzzzz. The death of the 4-4-2? The only thing dying here is me, from boredom.

While the sport has changed in all kinds of notable ways over the past 20 or so years, none of those obviously cherry-picked examples were as influential as the evolution of the fullback position. Nothing is new in this sport, but the current version of the trend began somewhere around the time Cafu and Roberto Carlos started playing together for Brazil in the late 1990s. It was then stamped into the historical record when Italy -- yes, Italy -- won the 2006 World Cup with Gianluca Zambrotta and Fabio Grosso blasting up and down the wings from deeper positions.

No longer does the international game create trends; it gets enveloped by them. But one simple way to understand the modern club game over the past 15 years is that the defining teams were the teams with the best attacking fullbacks.

At Barcelona, you had Jordi Alba on the left and Dani Alves on the right. At Real Madrid, it was Marcelo and Dani Carvajal. Bayern Munich had David Alaba and Phillip Lahm. Liverpool featured Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold. And after his first season in Manchester, Pep Guardiola realized he needed to get hip to the trend, too. City spent £118 million on fullbacks alone in the summer of 2018 and, well... you know how it's gone since then.

But then this season happened, and the rule turned inside out. Are you having a successful season? You must not be playing two attacking fullbacks at the same time. Are you going to leave the year with 30-something-fewer points than you had a year ago? Then you're a team coached by Jurgen Klopp, still featuring Robertson and Alexander-Arnold.

In fact, Liverpool's last two games suggest that even Klopp has realized the reality of soccer in 2023: you can't win with both of your fullbacks pushing high up the field.

The Disappearing Fullback

Since 2010, per Stats Perform's database, Jordi Alba has taken more touches inside the opposition penalty area in domestic play (724) than any other fullback across Europe's Big Five leagues. Second is Real Madrid's former left back, Marcelo (576), followed up by his fellow countrymen and former club rival Dani Alves (551). Robertson is fourth (481) and then Real Madrid's Carvajal is fifth (476). Alexander-Arnold is a bit deeper down (323), but Liverpool, Madrid and Barcelona are the only clubs with a left back and a right back with more than 300 penalty-area touches since 2010.

It's even more stark when you look at assists. Since 2010, only seven fullbacks have more than 30 assists in domestic play: Alba (62), Alves (52), Marcelo (46), Robertson (44), Alexander-Arnold, Carvajal and former Borussia Dortmund fullback Lukasz Piszczek (35).

This season, Liverpool and Dortmund (Raphael Guerreiro and Marius Wolff) are the only two teams with both a right back and a left back to register at least 30 touches in the opposition penalty area. So, what happened? Why aren't the biggest clubs in the world still pushing two fullbacks up into the attacking third?

The simplest explanation is that there are only so many players in the world who can essentially cover an entire flank by themselves, contribute in the attack, and not get exposed defensively over and over again. Liverpool, in a lot of ways, lucked into two of them: one was born in the city, the other turned into a world-class player almost immediately after leaving a relegated Hull City team for a meager transfer fee.

With Barcelona, Alba and Alves were two generationally unique players. For Madrid, Marcelo might be the best left-back... ever? At his peak, Carvajal was an absolute tank while at Bayern, Alaba and Lahm were maybe the two most positionally intelligent players alive.

These players are so hard to find, while the only other teams with the resources to afford a recognized, world-class attacking fullback are PSG and Manchester City. The former is still so obsessed with signing big-name attackers, aging midfielders and expensive defenders that they're unable to incorporate these kinds of players into a cohesive system. And despite City's big fullback spend in 2018, they haven't -- for a number of reasons -- been able to land on a consistent player-type in the role.

However, a scout and tactical analyst I spoke to suggested a couple of other reasons for the shift in fullback profiles that I think dovetail together: a need for balance and a lack of energy.

Where did they go?

If fullbacks aren't only pushing forward these days, then what are they doing?

Most top teams that play a four-man defense are doing one of two things: they're having one fullback hang back and pinch in as something like a third center-back, frequently asked to help progress the ball upfield from a hard-to-defend area that isn't quite in the center, but also isn't restricted by the sideline. Or they're having a fullback pinch into the midfield, next to their defensive midfielder, to provide additional cover.

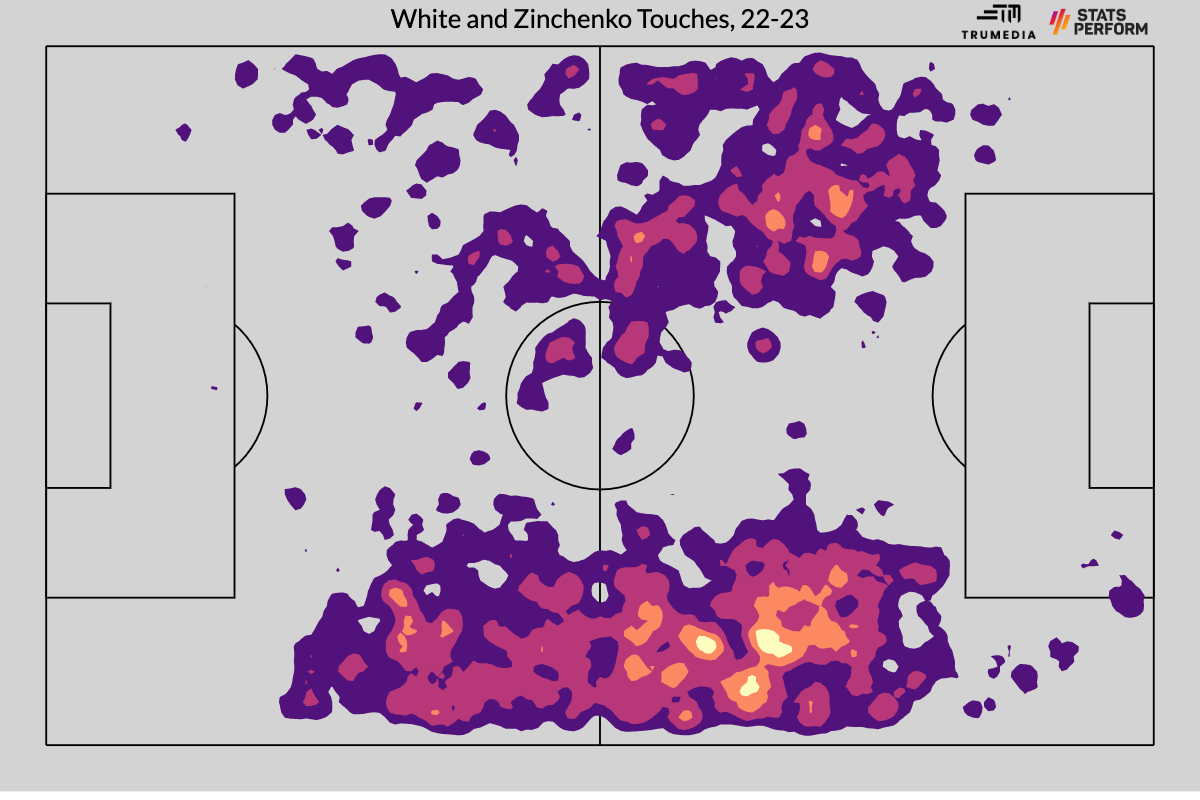

Current Premier League leaders Arsenal are doing both. Ben White doesn't overlap Bukayo Saka, while Oleksandr Zinchenko doesn't overlap Gabriel Martinelli. The former dictates play from a little deeper and has completed the second-most progressive passes and passes into the final third of any Arsenal player. Zinchenko, as you can see below, almost never gets on the ball near the sideline in his own half, or much in the attacking half, either. They both rarely extend their positioning beyond the edge of the opposition box.

The benefit of positioning your fullbacks like this is that it makes you less vulnerable to a counter-attack, whereby you lose possession in a bad spot and suddenly, two of your four defenders are behind the ball. Plus, it gives you more control over the ball and makes you less likely to turn it over and concede a counter-attack.

In the past, the teams with two high-flying fullbacks would frequently have their defensive midfielder drop into the space between the center backs -- both to provide an extra angle to move the ball up field and to ensure that there were at least three players behind the ball. However, doing this meant that there was one fewer body in the midfield to control and contest possession. By having a fullback slide into the midfield -- and another one stay connected to the center-backs -- teams are not only adding an extra body to the center of the field, but they're also not losing that defensive midfielder, either. They're going from two to four in the middle.

This creates another one of the major tactical trends of the season: the "box midfield," or two deeper midfielders with two midfielders ahead of them.

Since very few teams defend with four central midfielders, this creates a numerical advantage in the center. But it also allows both of the advanced midfielders to push forward into the space between the center forward and the wingers. This creates the same five-men-forward dynamic that we've seen in the past from teams that have both of their fullbacks push up to be inline with their three forwards. But it doesn't require the fullbacks -- or anyone else, for that matter -- to cover as much ground.

At City, Guardiola has completely done away with the pretense of fullbacks altogether. He's asked John Stones to step up from the back line alongside Rodri in the midfield, with Ilkay Gundogan and Kevin De Bruyne ahead of him. And if he's going to have his other defenders hang back, he figured, Why not just put my best defenders back there? Rather than having a full-back cosplay as a pinched-in center-back, he's settled on center backs like Manuel Akanji and Nathan Ake in his fullback roles.

Elsewhere, Newcastle's fullback pairing of Kieran Trippier and Dan Burn is a pretty clear example of one defensive and one attacking fullback. The same goes for Barcelona, who have frequently played either Ronald Araujo or Jules Kounde -- both considered center-backs as of a year ago -- in the right-back role. None of Real Madrid's full-backs have created two expected assists worthy of chances this season and while Bayern Munich now have both Alphonso Davies and Joao Cancelo on the roster, they don't play both of them at the same time.

Is the final holdout giving in?

At the highest level, soccer players have played more games over the past three years than ever before. With the coronavirus pandemic first throwing off and then radically compressing the schedule, plus the unprecedented mid-season World Cup last year, the demands on players have been extreme. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a lot of the teams having disappointing seasons this year are the ones who played the most games last year. The opposite of that is mostly true, too.

The attacking fullback role is arguably the most demanding of any position on the field, but it's not just demanding for the player himself; it's demanding for his teammates. The space he vacates has to be covered by midfielders and those covering midfielders then create other spaces that have to be covered by central defenders. And that's just with one attacking fullback. Put two out there, and the positional rotations essentially have no room for mental or physical error.

Elite fullbacks have always been hard to find, though that might be more true in 2023 than ever before. The players who have occupied these roles in the past have been through an extreme gauntlet of physical demands over the past three seasons, though the same goes for the players who've had to cover for them. With no one functioning at their physical peak right now, it makes sense that much of Europe has moved away from the roles that demand peak physical performance across the team.

And now, the manager and club that have demanded as much physical performance as anyone seem to have recognized it, too.

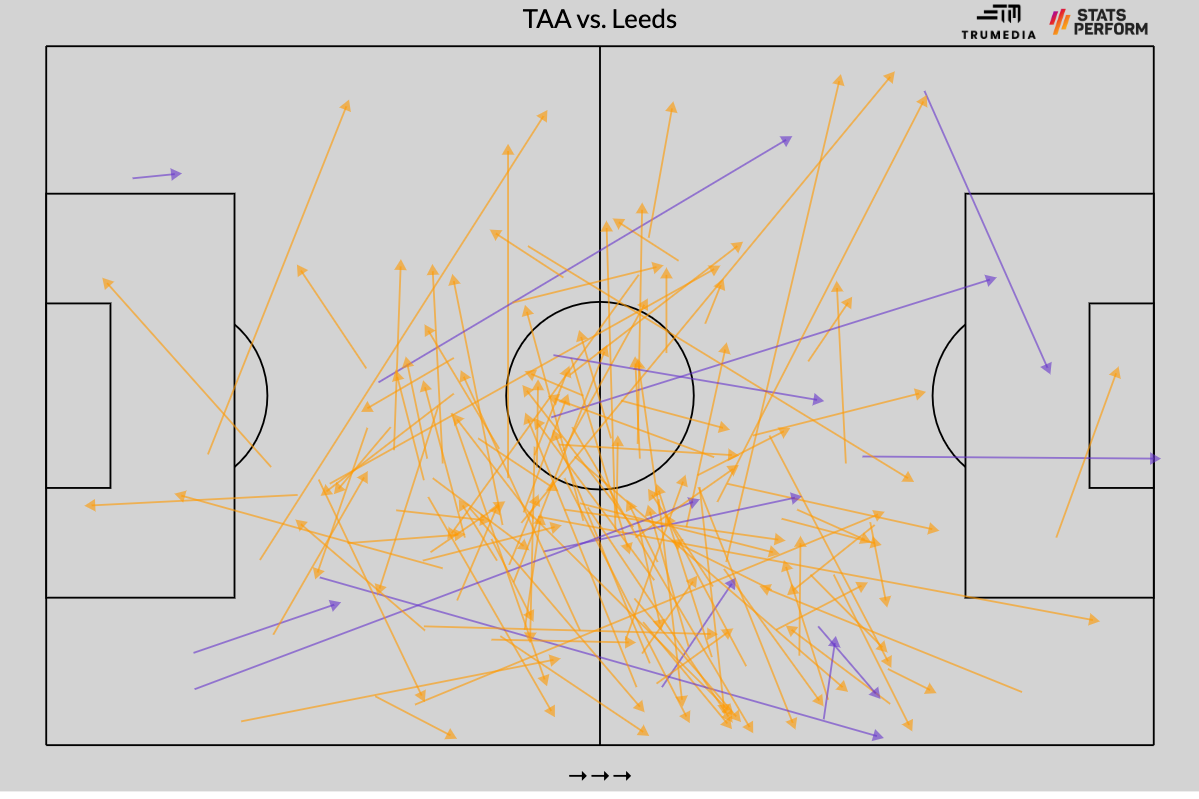

In Liverpool's last two matches, Trent Alexander-Arnold has slid frequently into the midfield -- next to Fabinho, rather than overlapping and interchanging with Mohamed Salah on the right wing. With something resembling that "box midfield" -- Fabinho and TAA behind Jordan Henderson and Curtis Jones or Thiago -- the second half of the Arsenal match through the entire Leeds game were probably Liverpool's 135-best consecutive minutes of the season.

The switch does two things. First, it gets Liverpool's best passer on the ball more often. Against Leeds, Alexander-Arnold took 153 touches -- the second-most of any player in the Premier League this season -- and he became just the fourth player since 2003-04 to register two assists and complete at least 90% of his 100-plus passes, along with star midfielders Paul Pogba, David Silva, and Santi Cazorla.

Such is Alexander-Arnold's skill on the ball that forcing him deeper doesn't limit his attacking impact, while it still allows him room to break forward if need be. Like everyone else who's doing it, the pinched-in fullback helps Liverpool control the ball a bit more, but more than that, it makes them less vulnerable to what has nearly destroyed their season: the high-speed counter-attack. Fabinho is no longer being left alone, on an island, in these moments since Alexander-Arnold isn't ahead of the ball when they lose it.

Asked after the Leeds game about the tactical tweak, Klopp said, "We need to be better protected because we have conceded too many counter-attacks ... For that, the formation suits us much better."

Of course, there have been plenty of other false dawns for Liverpool this season. Anyone else remember when they started playing a 4-4-2? But while Klopp's "gegenpressing" (or "counterpress") defined the previous era of the sport, he's now adopting one of the defining strategic trends of the current moment.

Will it work for them? It's too early to say, but it's certainly working pretty well for everyone else.